Why Small Organic Farms Are Going Under

A stated purpose of the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 (OFPA) (7 CFR § 6501-6522) is to assure consumers that organically produced products meet a consistent and uniform standard.

Currently, there are many issues plaguing the organic dairy industry that make this “consistent and uniform standard” impossible. Instead, family-scale organic dairies struggle to compete with industrialized dairies that are not following the letter or spirit of organic rules and regulations and seek to cash in on organic price premiums.

Currently, there are many issues plaguing the organic dairy industry that make this “consistent and uniform standard” impossible. Instead, family-scale organic dairies struggle to compete with industrialized dairies that are not following the letter or spirit of organic rules and regulations and seek to cash in on organic price premiums.

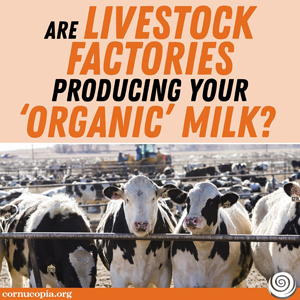

The crisis in organic dairy has been going on for a long time. In 2010, Cornucopia called out how factory-scale dairies were flooding the market with “organic” milk.

Cornucopia’s Dairy Report, The Industrialization of Organic Dairy, goes into detail on many of the ongoing problems—and their potential solutions.

WHAT IS ORGANIC LIVESTOCK FARMING?

What are organic requirements? Organic livestock farming has all the same prerequisites as other forms of organic farming. Overall, “organic production” is defined as a “production system that is managed to respond to site-specific conditions by integrating cultural, biological and mechanical practices that foster cycling of resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity.”

In general, organic food such as dairy must be produced under these requirements:

- Produce food without antibiotics or growth-promoting hormones (including rbGH/rbST)

- Free from the worst pesticides and herbicides, including dicamba and glyphosate (the primary ingredient in Roundup).

- Organic producers must “maintain or improve the natural resources of the operation, including soil and water quality” (7 CFR § 205.200). This means that the physical, hydrological, and biological features of a production operation, including soil, water, wetlands, woodlands, and wildlife, must be protected and fostered within the farm system (see 7 CFR § 205.200 for the definition of “natural resources”).

- Pasture for livestock must be managed like any other organic crop.

FAMILY-SCALE DAIRY FARMS IN CRISIS

Why are small dairy farms going out of business?

The organic industry has often been the stronghold of the family-scale farmer, and dairy farmers are no exception. Originally, the dairy industry was made up of smaller dairies, caring for no more than a hundred cows. In contrast, factory-scale dairies use several thousand cows at a time.

All over the U.S., family-scale dairies are struggling to make ends meet. Many have already lost their farms and businesses, some of which have been in the family for generations. For example, Wisconsin lost nearly two dairies a day in 2018, most of them family farms.

This loss is attributed to unfair competition from mega-farms.

Why did the price of milk go down?

Right now, there is a glut of organic milk on the market. This over-production has driven prices down.

Factory “organic” dairies have borrowed management practices from conventional CAFOs to produce more milk for less money. Although The Cornucopia Institute has filed numerous complaints with the USDA National Organic Program (NOP) over years, the USDA appears unwilling to enforce the intent and letter of the organic law.

In the organic marketplace it’s rare that the family-scale farmer will produce “too much” milk. Organic requirements to keep cows on pasture in season, as well as ensuring a minimum of 30% dry matter intake from pasture, is not a burden for smaller farms.

Can small dairy farms survive?

As of 2019, the USDA is doing very little to support the struggling family-scale organic dairy farmer. Instead, in their effort to support every scale of organic production, they are allowing factory dairies to operate on an uneven playing field.

As of 2019, the USDA is doing very little to support the struggling family-scale organic dairy farmer. Instead, in their effort to support every scale of organic production, they are allowing factory dairies to operate on an uneven playing field.

Consumers can support authentic organic dairy farms using The Cornucopia Institute’s Organic Dairy Scorecard.

THE ORIGIN OF LIVESTOCK

What is the Origin of Livestock Rule?

OFPA establishes that in general, organic livestock will be managed organically since the last third of gestation (7 CFR § 6509(b)). This means that the animals are generally required to be under organic management before they are born.

However, OFPA also includes an exception for dairy livestock, requiring a minimum period of one year of organic management before milk from non-organic dairy animals can be sold as organic (7 CFR § 6509(e)(2)).

The regulations regarding the origin of livestock also specify that all livestock products (including dairy) sold, labeled, or represented as being organic must be from livestock under continuous organic management from the last third of gestation onward (7 CFR § 205.236(a)). An exception for dairy animals is found in the regulation that allows for the transition of a dairy herd into organic production as long as they are under continuous organic management for the one-year period prior to production of organic milk or milk products (7 CFR § 205.236(a)(2)).

This is where problems have arisen.

How do farms cheat the Origin of Livestock Rule?

Due to a perceived loophole created by this language and inconsistent enforcement by accredited certifiers, some “organic” dairies are converting conventional cattle in perpetuity well beyond the initial transition of the farm from conventional to organic.

Essentially, massive factory farms buy one-year-old replacement animals and “convert” them to organic production on an ongoing basis. When those animals are “under continuous organic management” for the one-year period prior to freshening (the onset of milk production), these practices are considered within the bounds of the rules. They do not raise their own replacement animals—meaning calves born to their herd are sold into the conventional marketplace where they are raised on milk replacers and given antibiotics and feed laced in toxic chemicals and derived from genetically modified crops.

This practice is further detailed in Cornucopia’s Dairy Report, The Industrialization of Organic Dairy

The current rule that applies to transitioning organic livestock went into effect with the adoption of the original organic standards in 2002.

The law is clear in this area, despite some bad actors taking advantage of a perceived “loophole.” The preamble of the organic regulations makes it clear that continuously transitioning in conventional animals was not intended by the regulations. It states:

“Once an entire, distinct herd has been converted to organic production, all dairy animals shall be under organic management from the last third of gestation.”[1]

This preamble language is immortalized in the organic regulations, framed as an exception to the “continuous management” clause (7 CFR § 205.236(2)(iii)).

Many family-scale dairies are seriously impacted by this problem because they do raise their own calves—feeding them organic milk. It is up to three times more expensive to raise an organic calf than to raise a conventional calf.

This issue is contributing to the oversupply of milk and is also cutting off other viable income sources for many family-scale dairies. The continued transition of conventional animals increases the supply of animals able to produce organic milk, which in turn depresses the value of organic heifers and limits the incentives and benefits to producing organic replacement animals.

Previously, many true organic dairies supported their business by selling their calves as organic replacement animals when they did not need to replenish their own herds. Now that farms can take on much cheaper conventional stock and convert them to organic production, the market for high-quality organic dairy livestock has dried up.

The Twisted History Surrounding the Origin of Livestock Issue

The inconsistent application of origin of livestock rules and regulations are an ongoing problem.

Ten years ago the then-administrator of the NOP declared that the rule was a priority and said it would be the next rule the NOP would work on. At that time, they acknowledged the “two-track” method of getting animals into organic dairy production was problematic.

The “two-track” system refers to an April 2003 NOP statement that once an entire, distinct herd transitioned using the 80/20 provision (80% organic feed and 20% non-organic feed in the 12 months before milking), all offspring then had to be managed organically and no transitioned replacements could be purchased.[2]

Unfortunately, the NOP also stated that, for those that did not use the 80/20, whole-herd conversion, dairy animals only needed to be under continuous organic management 12 months prior to production (so producers could continue to transition animals into organic over time). This created further confusion and gaming of the system that continues to the present day.

The official “two-track” system was modified after a lawsuit was successful in arguing that allowing 20% non-organic feed went against OFPA (Harvey v. Veneman, 396 F.3d 28 (1st Cir. 2005)). However, this only changed the feed requirements. Dairy animals can still be transitioned from conventional to organic as a herd, transitioned from conventional to organic one at a time into an existing organic herd, or raised from gestation as organic.

On November 10, 2005, Congress amended the OFPA to add a provision for transitioning dairy livestock to organic production (7 USC § 6509(e)(2)(B)). The new provision allowed for dairy animals on the farm (during the 12-month period immediately prior to the sale of organic milk and milk products) to consume crops and forage from land included in the organic system plan (OSP) of a farm that was in the third year of organic management.

Between 1994 and 2006, the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) made six recommendations regarding origin of dairy animals. Some of these recommendations have been utilized by the USDA—but others have been ignored.

On December 21, 2000, the USDA published a final rule establishing the USDA organic regulations (65 FR 80548). At the same time, the origin of livestock provision was finalized, including the requirement that organic milk must be produced from animals under organic management beginning no later than one year prior to the production of organic milk or milk products.

The USDA published a proposed rule entitled “Revisions to Livestock Standards Based on Court Order” on April 27, 2006, intended to address the November 2005 amendments to OFPA (71 FR 24820). During the public comment period for that rulemaking, the USDA received nearly 12,400 comments on the issue of dairy animal replacement or origin of livestock issues. The same outpouring happened in response to the advance notice of proposed rulemaking on access to pasture (where they received over 325 comments on the issue) (71 FR 19131). Even though neither of these actions were aimed at the issue of origin of dairy livestock, it was clear that the public was invested in this issue and wanted it dealt with as soon as possible.

In July 2013, the USDA Office of Inspector General (OIG) published an audit report on organic milk operations.[3] They found that certifying agents were interpreting the origin of livestock requirements differently, leading to disparate practices throughout the organic dairy industry.

Despite this background and the intense interest from organic stakeholders in this issue, the NOP continued to be slow to act on the demands of the public.

The 2015 Proposed Rulemaking

In 2015, the NOP published a proposed rule on the origin of livestock issue. This proposal was put forward five years after the NOP said this issue was a top priority.

At the time, Cornucopia criticized the USDA for this rulemaking. There were some serious flaws embedded in the language of the proposal, including:

- Defining a dairy as “milking at least one cow.” This means that businesses could easily say they are dairies while serving a different purpose: working to transition conventional livestock to organic production over the required 12-month period. They would only need to have one dairy cow producing milk in the barn!

- Allowing “transitioned” (i.e. conventional) animals sourced from another certified organic dairy farm.

- Specifying, in the rule, that animals can only be transitioned one time per business, but then explicitly noting that new businesses can be started (essentially spelling out the loophole for bad actors).[4]

Because the proposed rule allowed transitioned animals sourced from another certified organic dairy farm—and organic dairy farms only had to be milking one cow—businesses could be run specifically for the purpose of cycling conventional animals into organic production without much difficulty. It would have effectively shifted the loophole.

The proposed rule would allow dairy farms—even those milking only one cow each—to convert hundreds or thousands of replacement animals from conventional to organic and sell them to organic dairy operations. These sales would likely be for a much lower price than authentic organic calves.

Public comment on the 2015 proposal was in favor of expediency in passing a rule on this issue, but commenters generally expressed concern about the problematic language. It appeared to many stakeholders that the proposed rule might further enshrine continuous cycling of conventional livestock into organic production.

Despite the NOP’s stated interest in this issue, the 2015 proposed rulemaking has languished for five additional years. In the meantime, the organic dairy industry has only become more divided. More family-scale farms have lost their businesses and their homes. The organic dairy crisis is in full swing.

The Current Status of The Origin of Livestock

At the spring NOSB meeting in April 2019, many dairy farmers and stakeholders spoke about the damage the origin of livestock problem continues to cause the industry. Although the NOSB itself offered many heartfelt comments and showed interest in settling the issue, the NOP suggested that it would still be many years before this problem is resolved.

PASTURE RULE

What is the pasture rule?

Cornucopia has a comprehensive article about the organic pasture rule, its history, and applications in real-world settings. The pasture rule sets the minimum benchmarks for grazing ruminant livestock animals on organically managed pastures.

In the regulations, both § 205.237 (Livestock feed) and § 205.239 (Livestock living conditions) dictate most of the pasture rule requirements.

The Current Pasturing Requirements

The organic pasture rules that affect organic dairies stand as summarized:

- Pasture is: “Land used for livestock grazing that is managed to provide feed value and maintain or improve soil, water, and vegetative resources” (7 CFR § 205.2).

- Dairy animals must graze pasture during the entire “grazing season,” a minimum of 120 days per year.

- Livestock must get a minimum of 30% dry matter intake (DMI) from pasture during the grazing season. “Dry matter” is defined as: “The amount of a feedstuff remaining after all the free moisture is evaporated out.” (7 CFR § 205.2).

- Producers must have a pasture management plan, requiring producers to manage their pasture like they would a crop to meet their animals’ feed requirements and to protect soil and water quality (which are negatively affected by overgrazing).

These changes set the minimum bar for organic dairy production.

Lack of Enforcement for the Pasture Rule

The pasture requirements for organic livestock are not difficult to meet: they require 30% dry matter intake (DMI) and a minimum 120-day grazing season for each individual animal. This is an extremely low bar for ruminant animals that evolved to subsist entirely on grazing.

Despite this, there are still massive dairies scraping by at 30% DMI and barely meeting the grazing season requirement. Since calculating DMI is not always an exact science (although dedicated farms utilize tools that improve their calculations), it is probable and even confirmed by insider investigations that some of these large dairies are not even meeting this minimum standard. This means the cows live most of their lives in feedlots, subsisting on grain and stored forages (like hay or silage).

As with the Origin of Livestock issue, operations that game the system create an unfair playing field.

IMPORTED FEED

What’s wrong with imported feeds?

Imported grains are a problem for the domestic organic marketplace due to fraud and lack of oversight. Huge quantities of imported grain coming into U.S. ports as organic may not actually be organic—meaning it was grown with conventional pesticides and/or genetically modified organisms. This outright fraud has been exposed by the Washington Post and by Cornucopia’s own researchers.

Cornucopia’s white paper, The Turkish Infiltration of the U.S. Organic Grain Market: How Failed Enforcement and Ineffective Regulations Made the U.S. Ripe for Fraud and Organized Crime, outlines the pathways for organic import fraud via Turkey. The reported organic acreage from Turkey and many Eastern European countries does not support the tonnage imported into the U.S. In other words, available data shows we are importing more “organic” grain than they are growing.

Factory dairies buy this fraudulent feed for much cheaper than they can acquire domestic grain, although the incredibly low feed prices raise questions about the organic integrity of the grain.

Ethical domestic dairies that rely on pasture and farm-grown feed or other legitimate sources of organic grain are disadvantaged by their higher feed costs and by the artificially low prices of factory-organic milk in the marketplace.

To learn more about the issues of grain fraud, read Cornucopia’s comprehensive report: Against the Grain: Protecting Organic Shoppers against Import Fraud and Farmers from Unfair Competition.

GRASS-FED DAIRY

What does grass-fed dairy mean?

The term “grass-fed” simply means the cattle ate grass at some point in their lives. It does not legally mean the cattle ate only grass or were even finished on grass.

If someone is interested in dairy (or beef) that is grass-fed, it is important to carefully consider the product’s labeling claims. There are also third-party labels that seek to label different “grass fed” products, with slightly differing standards.

The fundamental difference between industrial-organic dairy and grass-based, family-scale organic dairy is how the cows are fed.

Is there a difference between organic and grass-fed?

All organic dairy is technically grass-fed, but not necessarily 100% grass-fed. It’s important to know the difference between these two designations because an animal’s diet affects the nutrient profile of the milk, as well as livestock health and well-being.

Industrial operations feed grain to their cattle, which promotes a higher milk production than grazing can alone. Increasing the amount of grain and other concentrated feeds (such as molasses, soy, and oils) goes hand-in-hand with restricting grazing. Operators can make more money from the increased milk production, but the nutrient profile of the milk may be similar to conventional milk.

Milk can be a good source of beneficial omega-3 fatty acids if the livestock graze on pasture for all, or the majority of, their diet. This includes a high ratio of conjugated linoleic acids (CLAs).

Pasturing and a diet composed mostly or even entirely of forage is better for cows’ health overall.

As ruminants, cattle evolved to eat mainly grass and other fresh vegetation. The microbiome in the rumen, a part of their digestive systems, excels at breaking down fiber to provide the animal with easily absorbed nutrients. Eating grain disrupts the normal digestive process, changing the pH in the rumen, resulting in physiological stress.

This “acidosis” from grain-based diets facilitates the growth of harmful microorganisms, including dangerous strains of E. coli, and metabolic disease in animals. Feeding cattle a diet composed primarily of grass not only prevents acidosis and its associated health problems, but grazing promotes cattle’s overall physical and mental health and creates safer food products.

The highest quality dairy available at retail will bear both the “100% grass-fed” label and the organic seal.

STORE BRANDS

Store brands, also known as “private-label brands,” are branded by grocery chains. Typically, these businesses buy finished or packaged products wholesale and then label those products with their own brand. Popular examples of this business model include Safeway’s “O Organics,” Whole Foods’ “365,” and Aldi’s “Friendly Farms.” Familiar businesses continue to expand into the organic market under their own private-label brands.

The inherent problem with private labels is that they lack transparency. Grocery chains or distributors lower their prices because the source of their food changes depending on who offers the lowest price at the time. The consumer will never know there was a change in suppliers. Are these products coming from family farms? Are they certified organic by reputable accredited certifiers? Are they joining a long list of other organic products being imported from overseas?

This lack of transparency defies the organic consumer’s desire to understand where their food comes from and how it is produced. In 2006, when the Cornucopia’s original Organic Dairy Report was published, over 80% of the name-brand organic dairy marketers responded to our survey, but only a handful of the private-label brands responded. In 2016, no private-label brands responded to Cornucopia’s dairy survey, signaling their desire to remain, well, private.

Examples: where store brands become problematic

Some of the worst offenders in the organic dairy industry supply store brands. One of these is Natural Prairie Dairy, an operation that apparently provides milk for the organic store brands of Kroger and Meijer.

|

In 2015, The Cornucopia Institute launched an investigation of “organic” factory dairies. Our flyover investigations found Natural Prairie Dairy stocking their pastures at an unsustainable rate (when the cattle were grazing at all), calling into question their legitimacy as an organic dairy. Other investigative work found that Natural Prairie Dairy was selling off their baby cows at birth and purchasing converted, conventional heifers.

Unfortunately, Natural Prairie Dairy never cleaned up their act (implicating their organic certifier, the Texas Department of Agriculture, since they continued to certify this bad actor). In 2019, the animal rights direct-action group Animal Recovery Mission exposed horrific animal abuse at Natural Prairie Dairy during an undercover investigation.

Because factory farms like Natural Prairie Dairy provide the very cheapest “organic” dairy on the market, they are potential sources of milk for “organic” store brands.

WHAT CAN CONSUMERS DO?

When buying certified organic food, the price premium should support environmental stewardship, humane animal welfare, and financial stability for family-scale farms. The failure of the USDA to enforce the organic rules and the intent of the organic law—including the pasture rule and the origin of livestock—means consumers are the last line of defense for many high-integrity family farms.

Organic dairy consumers can educate themselves to ensure the products and farms they support reflect their expectations for the organic seal.

High-quality milk and other dairy products from confirmed high-integrity dairies is more expensive because authentic organic production is more expensive.

The extra money at the checkout is an investment in environmental, animal, and human health.

What are the best brands to buy to help save authentic organic farms?

The best choice is organic milk from independent brands that score five or four cows on Cornucopia’s Organic Dairy Scorecard. These products come from family-scale farms dedicated to organic practices.

Where should I buy milk to support ethical organic dairy farmers?

Cornucopia only rates brands available at retail. If you can’t find a five- or four-cow brand in your local co-op or grocery store, you may consider looking for organic family farms in your area. Some sell direct-to-consumer from farms or farmers markets, and they are typically transparent in their practices.

Cornucopia always recommends certified organic, local farms with grass-fed cows first, but if one is not available, Cornucopia’s DIY Certification Guide can help you ask farmers the kinds of insightful questions that an organic certifying agent would ask when inspecting an organic farm. The guide helps ensure you are rewarding the most ethical farmers who care for their animals and the land, while bringing home the healthiest food for your family.

With many of the most ethical organic dairy farms facing pressure from increased industrialization, it is now more important than ever for consumers to “vote with their forks.”

When consumers become informed about organic dairy production practices and learn of the gulf between livestock factories and authentic organic dairies, they can make decisions to support ethical farms, sending a strong message to those who are bending the organic rules.

Together, consumers can make profound changes to the industry by supporting family-scale organic dairies and shunning livestock factories.

[1] “Federal Register Volume 65, Number 246 – Preamble, Subpart: Livestock Production.” December 21, 2000. US Federal Register, page 80560. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2000-12-21/html/00-32257.htm

[2] National Organic Program. April 11, 2003. “Origin of Livestock Statement.” Available online at www.regulations.gov under “Related Documents” for docket number AMS-NOP-11-0009.

[3] Office of Inspector General. July, 2013. “Audit report on organic milk operations.” http://www.usda.gov/ oig/ webdocs/ 01601-0002-32.pdf.

[4] The exact language in the 2015 proposed rulemaking was as follows: “Dairy animals. A producer as defined in § 205.2 may transition dairy animals into organic production only once. A producer is eligible for this transition only if the producer starts a new organic dairy farm or converts an existing nonorganic dairy farm to organic production.”